Oracle

| Part of a series on |

| Anthropology of religion |

|---|

|

| Social and cultural anthropology |

An oracle is a person or thing considered to provide insight, wise counsel or prophetic predictions, most notably including precognition of the future, inspired by deities. If done through occultic means, it is a form of divination.

Description[edit]

The word oracle comes from the Latin verb ōrāre, "to speak" and properly refers to the priest or priestess uttering the prediction. In extended use, oracle may also refer to the site of the oracle, and to the oracular utterances themselves, called khrēsmoí (χρησμοί) in Greek.

Oracles were thought to be portals through which the gods spoke directly to people. In this sense, they were different from seers (manteis, μάντεις) who interpreted signs sent by the gods through bird signs, animal entrails, and other various methods.[1]

The most important oracles of Greek antiquity were Pythia (priestess to Apollo at Delphi), and the oracle of Dione and Zeus at Dodona in Epirus. Other oracles of Apollo were located at Didyma and Mallus on the coast of Anatolia, at Corinth and Bassae in the Peloponnese, and at the islands of Delos and Aegina in the Aegean Sea.

The Sibylline Oracles are a collection of oracular utterances written in Greek hexameters, ascribed to the Sibyls, prophetesses who uttered divine revelations in frenzied states.

Origins[edit]

Walter Burkert observes that "Frenzied women from whose lips the God speaks" are recorded in the Near East as in Mari in the second millennium BC and in Assyria in the first millennium BC.[2] In Egypt, the goddess Wadjet (eye of the moon) was depicted as a snake-headed woman or a woman with two snake-heads. Her oracle was in the renowned temple in Per-Wadjet (Greek name Buto). The oracle of Wadjet may have been the source for the oracular tradition which spread from Egypt to Greece.[3] Evans linked Wadjet with the "Minoan Snake Goddess".[4]

At the oracle of Dodona she is called Diōnē (the feminine form of Diós, genitive of Zeus; or of dīos, "godly", literally "heavenly"), who represents the earth-fertile soil, probably the chief female goddess of the proto-Indo-European pantheon[citation needed]. Python, daughter (or son) of Gaia was the earth dragon of Delphi represented as a serpent and became the chthonic deity, enemy of Apollo, who slew her and possessed the oracle.[5]

In classical antiquity[edit]

Pythia at Delphi[edit]

When the Prytanies' seat shines white in the island of Siphnos,

White-browed all the forum—need then of a true seer's wisdom—

Danger will threat from a wooden boat, and a herald in scarlet.

The Pythia was the mouthpiece of the oracles of the god Apollo, and was also known as the Oracle of Delphi.[7]

The Delphic Oracle exerted considerable influence throughout Hellenic culture. Distinctively, this woman was essentially the highest authority both civilly and religiously in male-dominated ancient Greece. She responded to the questions of citizens, foreigners, kings, and philosophers on issues of political impact, war, duty, crime, family, laws—even personal issues.[8] The semi-Hellenic countries around the Greek world, such as Lydia, Caria, and even Egypt also respected her and came to Delphi as supplicants.

Croesus, king of Lydia beginning in 560 BC, tested the oracles of the world to discover which gave the most accurate prophecies. He sent out emissaries to seven sites who were all to ask the oracles on the same day what the king was doing at that very moment. Croesus proclaimed the oracle at Delphi to be the most accurate, who correctly reported that the king was making a lamb-and-tortoise stew, and so he graced her with a magnitude of precious gifts.[9] He then consulted Delphi before attacking Persia, and according to Herodotus was advised: "If you cross the river, a great empire will be destroyed". Believing the response favourable, Croesus attacked, but it was his own empire that ultimately was destroyed by the Persians.

She allegedly also proclaimed that there was no man wiser than Socrates, to which Socrates said that, if so, this was because he alone was aware of his own ignorance. After this confrontation, Socrates dedicated his life to a search for knowledge that was one of the founding events of western philosophy. He claimed that she was "an essential guide to personal and state development."[10] This oracle's last recorded response was given in 362 AD, to Julian the Apostate.[11]

The oracle's powers were highly sought after and never doubted. Any inconsistencies between prophecies and events were dismissed as failure to correctly interpret the responses, not an error of the oracle.[12] Very often prophecies were worded ambiguously, so as to cover all contingencies – especially so ex post facto. One famous such response to a query about participation in a military campaign was "You will go you will return never in war will you perish". This gives the recipient liberty to place a comma before or after the word "never", thus covering both possible outcomes. Another was the response to the Athenians when the vast army of king Xerxes I was approaching Athens with the intent of razing the city to the ground. "Only the wooden palisades may save you"[citation needed], answered the oracle, probably aware that there was sentiment for sailing to the safety of southern Italy and re-establishing Athens there. Some thought that it was a recommendation to fortify the Acropolis with a wooden fence and make a stand there. Others, Themistocles among them, said the oracle was clearly for fighting at sea, the metaphor intended to mean war ships. Others still insisted that their case was so hopeless that they should board every ship available and flee to Italy, where they would be safe beyond any doubt. In the event, variations of all three interpretations were attempted: some barricaded the Acropolis, the civilian population was evacuated over sea to nearby Salamis Island and to Troizen, and the war fleet fought victoriously at Salamis Bay. Should utter destruction have happened, it could always be claimed that the oracle had called for fleeing to Italy after all.

Sibyl at Cumae[edit]

Cumae was the first Greek colony on the mainland of Italy, near Naples, dating back to the 8th century BC. The sibylla or prophetess at Cumae became famous because of her proximity to Rome and the Sibylline Books acquired and consulted in emergencies by Rome wherein her prophecies were transcribed. The Cumaean Sibyl was called "Herophile" by Pausanias and Lactantius, "Deiphobe, daughter of Glaucus" by Virgil, as well as "Amaltheia", "Demophile", or "Taraxandra" by others. Sibyl's prophecies became popular with Christians as they were thought to predict the birth of Jesus Christ.

Oracle at Didyma[edit]

Didyma near Ionia in Asia Minor in the domain of the famous city of Miletus.

Oracle at Dodona[edit]

Dodona in northwestern Greece was another oracle devoted to the Mother Goddess identified at other sites with Rhea or Gaia, but here called Dione. The shrine of Dodona, set in a grove of oak trees, was the oldest Hellenic oracle, according to the fifth-century historian Herodotus, and dated from pre-Hellenic times, perhaps as early as the second millennium BC, when the tradition may have spread from Egypt. By the time of Herodotus, Zeus had displaced the Mother Goddess, who had been assimilated to Aphrodite, and the worship of the deified hero Heracles had been added. Dodona became the second most important oracle in ancient Greece, after Delphi. At Dodona, Zeus was worshipped as Zeus Naios or Naos (god of springs Naiads, from a spring under the oaks), or as Zeus Bouleos (chancellor). Priestesses and priests interpreted the rustling of the leaves of the oak trees by the wind to determine the correct actions to be taken[citation needed].

Oracle at Abae[edit]

The oracle of Abae was one of the most important oracles. It was almost completely destroyed by the Persians during the Second Persian invasion of Greece.[13]

Other oracles[edit]

Erythrae near Ionia in Asia Minor was home to a prophetess.

Trophonius was an oracle at Lebadea of Boeotia devoted to the chthonian Zeus Trophonius. Trophonius was a Greek hero nursed by Europa.[14]

Near the Menestheus's port or Menesthei Portus (Greek: Μενεσθέως λιμήν), modern El Puerto de Santa María, Spain, was the Oracle of Menestheus (Greek: Μαντεῖον τοῦ Μενεσθέως), to whom also the inhabitants of Gades offered sacrifices.[15][16]

At the Ikaros island in the Persian Gulf (modern Failaka Island in Kuwait), there was an oracle of Artemis Tauropolus.[17]

At Claros, there was the oracle of Apollo Clarius.[18]

At Ptoion, there was an oracle of Ptoios and later of Apollo.[19]

At Gryneium, there was a sanctuary of Apollo with an ancient oracle.[20][21][22]

At Livadeia there was the oracle of Trophonius.[23]

The oracle of Zeus Ammon at Siwa Oasis was so famous that Alexander the Great visited it when he conquered Egypt.

There was also another oracle of Zeus Ammon at Aphytis in Chalkidiki.[24]

The oracle of Zeus at Olympia.[25]

In the city of Anariace (Ἀναριάκη) at the Caspian Sea, there was an oracle for sleepers. Persons should sleep in the temple in order to learn the divine will.[26][27][28]

The oracle of Apollo at Eutresis[29] and the oracle of Apollo at Tegyra.[30]

Oracle of Aphrodite at Paphos.[31]

There were many "oracles of the dead", such as in Argolis, Cumae, Herakleia in Pontos, in the Temple of Poseidon in Taenaron, but the most important was the Necromanteion of Acheron.

In other cultures[edit]

The term "oracle" is also applied in modern English to parallel institutions of divination in other cultures. Specifically, it is used in the context of Christianity for the concept of divine revelation, and in the context of Judaism for the Urim and Thummim breastplate, and in general any utterance considered prophetic.[32]

Celtic polytheism[edit]

In Celtic polytheism, divination was performed by the priestly caste, either the druids or the vates. This is reflected in the role of "seers" in Dark Age Wales (dryw) and Ireland (fáith).

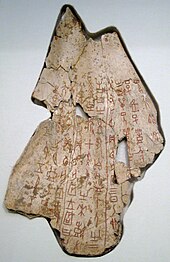

China[edit]

In China, oracle bones were used for divination in the late Shang dynasty, (c. 1600–1046 BC). Diviners applied heat to these bones, usually ox scapulae or tortoise plastrons, and interpreted the resulting cracks.

A different divining method, using the stalks of the yarrow plant, was practiced in the subsequent Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BC). Around the late 9th century BC, the divination system was recorded in the I Ching, or "Book of Changes", a collection of linear signs used as oracles. In addition to its oracular power, the I Ching has had a major influence on the philosophy, literature and statecraft of China since the Zhou period.

Hawaii[edit]

In Hawaii, oracles were found at certain heiau, Hawaiian temples. These oracles were found in towers covered in white kapa cloth made from plant fibres. In here, priests received the will of gods. These towers were called 'Anu'u. An example of this can be found at Ahu'ena heiau in Kona.[33]

India and Nepal[edit]

In ancient India, the oracle was known as ākāśavānī "voice/speech from the sky/aether" or aśarīravānī "a disembodied voice (or voice of the unseen)" (asariri in Tamil), and was related to the message of a god. Oracles played key roles in many of the major incidents of the epics Mahabharata and Ramayana. An example is that Kamsa (or Kansa), the evil uncle of Krishna, was informed by an oracle that the eighth son of his sister Devaki would kill him. The opening verse of the Tiruvalluva Maalai, a medieval Tamil anthology usually dated by modern scholars to between c. 7th and 10th centuries CE, is attributed to an asariri or oracle.[34]: 58–59 [35]: 16 [36] However, there are no references in any Indian literature of the oracle being a specific person.

Contemporarily, Theyyam or "theiyam" in Malayalam - a south Indian language - the process by which a Priest invites a Hindu god or goddess to use his or her body as a medium or channel and answer other devotees' questions, still happens.[37] The same is called "arulvaakku" or "arulvaak" in Tamil, another south Indian language - Adhiparasakthi Siddhar Peetam is famous for arulvakku in Tamil Nadu.[38] The people in and around Mangalore in Karnataka call the same, Buta Kola, "paathri" or "darshin"; in other parts of Karnataka, it is known by various names such as, "prashnaavali", "vaagdaana", "asei", "aashirvachana" and so on.[39][40][41][42][43] In Nepal it is known as, "Devta ka dhaamee" or "jhaakri".[44]

Nigeria[edit]

The Igbo people of southeastern Nigeria in Africa have a long tradition of using oracles. In Igbo villages, oracles were usually female priestesses to a particular deity, usually dwelling in a cave or other secluded location away from urban areas, and, much as the oracles of ancient Greece, would deliver prophecies in an ecstatic state to visitors seeking advice. Two of their ancient oracles became especially famous during the pre-colonial period: the Agbala oracle at Awka and the Chukwu oracle at Arochukwu.[45] Although the vast majority of Igbos today are Christian, many of them still use oracles.

Among the related Yoruba peoples of the same country, the Babalawos (and their female counterparts, the Iyanifas) serve collectively as the principal aspects of the tribe's world-famous Ifa divination system. Due to this, they customarily officiate at a great many of its traditional and religious ceremonies.

Norse mythology[edit]

In Norse mythology, Odin took the severed head of the god Mimir to Asgard for consultation as an oracle. The Havamal and other sources relate the sacrifice of Odin for the oracular runes whereby he lost an eye (external sight) and won wisdom (internal sight; insight).

Pre-Columbian Americas[edit]

In the migration myth of the Mexitin, i.e., the early Aztecs, a mummy-bundle (perhaps an effigy) carried by four priests directed the trek away from the cave of origins by giving oracles. An oracle led to the foundation of Mexico-Tenochtitlan. The Yucatec Mayas knew oracle priests or chilanes, literally 'mouthpieces' of the deity. Their written repositories of traditional knowledge, the Books of Chilam Balam, were all ascribed to one famous oracle priest who had correctly predicted the coming of the Spaniards and its associated disasters.[citation needed]

Tibet[edit]

In Tibet, oracles (Chinese: 护法) have played, and continue to play, an important part in religion and government. The word "oracle" is used by Tibetans to refer to the spirit that enters those men and women who act as media between the natural and the spiritual realms. The media are, therefore, known as kuten, which literally means, "the physical basis". In the 29-Article Ordinance for the More Effective Governing of Tibet (Chinese: 欽定藏內善後章程二十九條[46]), an imperial decree published in 1793 by the Qianlong Emperor, article 1 states that the creation of Golden Urn is to ensure prosperity of Gelug, and to eliminate cheating and corruption in the selection process performed by oracles.[47]

The Dalai Lama, who lives in exile in northern India, still consults an oracle known as the Nechung Oracle, which is considered the official state oracle of the government of Tibet. The Dalai Lama has, according to centuries-old custom, consulted the Nechung Oracle during the new year festivities of Losar.[48] Nechung and Gadhong are the primary oracles currently consulted; former oracles such as Karmashar and Darpoling are no longer active in exile. The Gadhong oracle has died leaving Nechung to be the only primary oracle. Another oracle the Dalai Lama consults is the Tenma Oracle, for which a young Tibetan woman by the name of Khandro La is the medium for the mountain goddesses Tseringma along with the other 11 goddesses. The Dalai Lama gives a complete description of the process of trance and spirit possession in his book Freedom in Exile.[49] Dorje Shugden oracles were once consulted by the Dalai Lamas until the 14th Dalai Lama banned the practice, even though he consulted Dorje Shugden for advice to escape and was successful in it. Due to the ban, many of the abbots that were worshippers of Dorje Shugden have been forced to go against the Dalai Lama.

See also[edit]

- Fuji (planchette writing)

- Futomani

- I Ching

- Jiaobei

- Kau Cim

- Lên đồng

- Lingqijing

- Mudang

- Poe divination

- Tangki

- Tung Shing

References[edit]

- ^ Flower, Michael Attyah. The Seer in Ancient Greece. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008.

- ^ Walter Burkert.Greek Religion. Harvard University Press.1985.p 116-118

- ^ Herodotus, The Histories, ii 55, and vii 134.

- ^ Cristopher L.C. Whitcomp.Minoan Snake goddess.8.Snakes, Egypt, Magic and wome

- ^ Hymn to Pythian Apollo.363,369

- ^ Herodotus, The Histories, as translated in: Rawlinson, George; Rawlinson, Henry Creswicke; Wilkinson, John Gardner (1862). The History of Herodotus: A New English Version. Vol. II. London: John Murray. p. 376. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ Plato, G.M.A. Grube, J.M. Cooper - The Trial and Death of Socrates (Third Edition): "Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, Death Scene from Phaedo" (page 24 - footnote 7) Hackett Publishing, 2000; ISBN 1603846476 [Retrieved 2015-04-25]

- ^ Broad, W. J. (2007), p.43

- ^ Broad, W. J. (2007), p.51-53

- ^ Broad, W. J. (2007), p.63. Socrates also argued that the oracle's effectiveness was rooted in her ability to abandon herself completely to a higher power by way of insanity or "sacred madness."

- ^ Thomas, Carol G. (1988). Paths from Ancient Greece. Brill Publishers. p. 47. ISBN 9004088466.

- ^ Broad, W. J. (2007), p.15

- ^ Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Abae

- ^ Pausanias.Guide to Greece 9.39.2–5.

- ^ "LacusCurtius • Strabo's Geography — Book III Chapter 1". penelope.uchicago.edu.

- ^ "Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography (1854), MENESTHEI PORTUS". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- ^ "Strabo, Geography, §16.3.2".

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece 7.5.1–3

- ^ "Apollo Ptoion sanctuary, Anne Jacquemin - Wiley Online Library". Wiley. 21 January 2013. doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah30160.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Stephanus of Byzantium, Ethnica, G213.10".

- ^ "Philostratus the Athenian, Vita Apollonii, 4.14".

- ^ "Strabo, Geography, 13.3.5".

- ^ Col. William Leake, TRAVELS IN NORTHERN GREECE, 2.121

- ^ Stephanus of Byzantium, Ethnica, A151.1

- ^ A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Oraculum

- ^ Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography (1854), Anariacea

- ^ Strabo, Geography, 11.7.1

- ^ Stephanus of Byzantium, Ethnica, A93.5

- ^ Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Eutresis

- ^ Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography (1854), Tegyra

- ^ C. Suetonius Tranquillus, Divus Titus, 5

- ^ OED s.v. "oracle n."

- ^ John Fischer. "'Anu'u (oracle tower) and Ki'i Akua (temple images) at 'Ahu'ena Heiau in Kailua-Kona on Hawaii's Big Island". About.com Travel.

- ^ Kamil Zvelebil (1975). Tamil Literature. Handbook of Oriental Studies. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-04190-7.

- ^ S. N. Kandasamy (2020). திருக்குறள்: ஆய்வுத் தெளிவுரை (பெருட்பால், பகுதி 1) [Tirukkural: Research commentary: Book of Porul, Part 1]. Chennai: Manivasagar Padhippagam.

- ^ Vedhanayagam, Rama (2017). திருவள்ளுவ மாலை மூலமும் எளிய உரை விளக்கமும் [Tiruvalluvamaalai: Source with simple commentary] (in Tamil) (1 ed.). Chennai: Manimekalai Prasuram.

- ^ "'Devakoothu'; the lone woman Theyyam in North Malabar". Mathrubhumi.

- ^ Nanette R. Spina (2017) (28 February 2017), Women's Authority and Leadership in a Hindu Goddess Tradition, Springer, p. 135, ISBN 978-1-1375-8909-5

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Brückner, Heidrun (1987). "Bhuta Worship in Coastal Karnataka: An Oral Tulu Myth and Festival Ritual of Jumadi". Studien zur Indologie und Iranistik. 13/14: 17–37.

- ^ Brückner, Heidrun (1992). "Dhumavati-Bhuta" An Oral Tulu-Text Collected in the 19th Century. Edition, Translation, and Analysis". Studien zur Indologie und Iranistik. 13/14: 13–63.

- ^ Brückner, Heidrun (1995). Fürstliche Fest: Text und Rituale der Tuḷu-Volksreligion an der Westküste Südindiens. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. pp. 199–201.

- ^ Brückner, Heidrun (2009a). On an Auspicious Day, at Dawn … Studies in Tulu Culture and Oral Literature. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- ^ Brückner, Heidrun (2009b). "Der Gesang von der Büffelgottheit" in Wenn Masken Tanzen – Rituelles Theater und Bronzekunst aus Südindien edited by Johannes Beltz. Zürich: Rietberg Museum. pp. 57–64.

- ^ Gulia, Kuldip Singh (2005). Human Ecology of Sikkim – A Case Study of Upper Rangit Basin. Delhi, India: Kalpaz Publications. pp. 152–154, 168. ISBN 978-81-7835-325-8.

- ^ Webster J.B. and Boahen A.A., The Revolutionary Years, West Africa since 1800, Longman, London, p. 107–108.

- ^ "欽定藏內善後章程/欽定藏內善後章程二十九條". zh.wikisource.org.

- ^ 皇帝為了黃教的興隆,和不使護法弄假作弊

- ^ Gyatso, Tenzin (1988). Freedom in Exile: the Autobiography of the Dalai Lama of Tibet. Fully revised and updated. Lancaster Place, London, UK: Abacus Books (A Division of Little, Brown and Company UK). ISBN 0-349-11111-1. p.233

- ^ "Nechung - the State Oracle of Tibet". Archived from the original on 2006-12-05. Retrieved 2007-01-23.

Further reading[edit]

- Broad, William J. (2007). The Oracle: Ancient Delphi and the Science Behind Its Lost Secrets. New York: Penguin Press.

- Broad, William J. (2006). The Oracle: The Lost Secrets and Hidden Message of Ancient Delphi. New York: Penguin Press.

- Curnow, T. (1995). The Oracles of the Ancient World: A Comprehensive Guide. London: Duckworth – ISBN 0-7156-3194-2

- Evans-Pritchard, E. (1976). Witchcraft, Oracle, and Magic among the Azande. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Fontenrose, J. (1981). The Delphic Oracle: Its Responses and Operations, with a Catalogue of Responses. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Kajava, Mika (ed.) (2013). Studies in Ancient Oracles and Divination (Acta Instituti Romani Finlandiae 40). Rome: Institutum Romanum Finlandiae.

- Smith, Frederick M. (2006). The Self-Possessed: Deity and Spirit Possession in South Asian Literature. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-13748-6.

- Stoneman, Richard (2011). The Ancient Oracles: Making the Gods Speak. Yale University Press.

- Garoi Ashram, (2004–2023). The Copper Oracle of Sri Achyuta: Answers as Instantaneous Inscription.

- Woodard, Roger D. (2023). Divination and prophecy in the ancient Greek world. Cambridge, United Kingdom. ISBN 9781009221610.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links[edit]

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.